Cycles of Art

Upcycling. Repurposing. Creative reuse. No matter what they choose to call it, innovative artists are adorning their work with discarded objects, and for a variety of reasons: a commitment to sustainability, a fondness for nostalgia, or a lifelong obsession they can’t quite explain.

Here are some of the creative forces blazing a path in upcycled art.

Federico Uribe

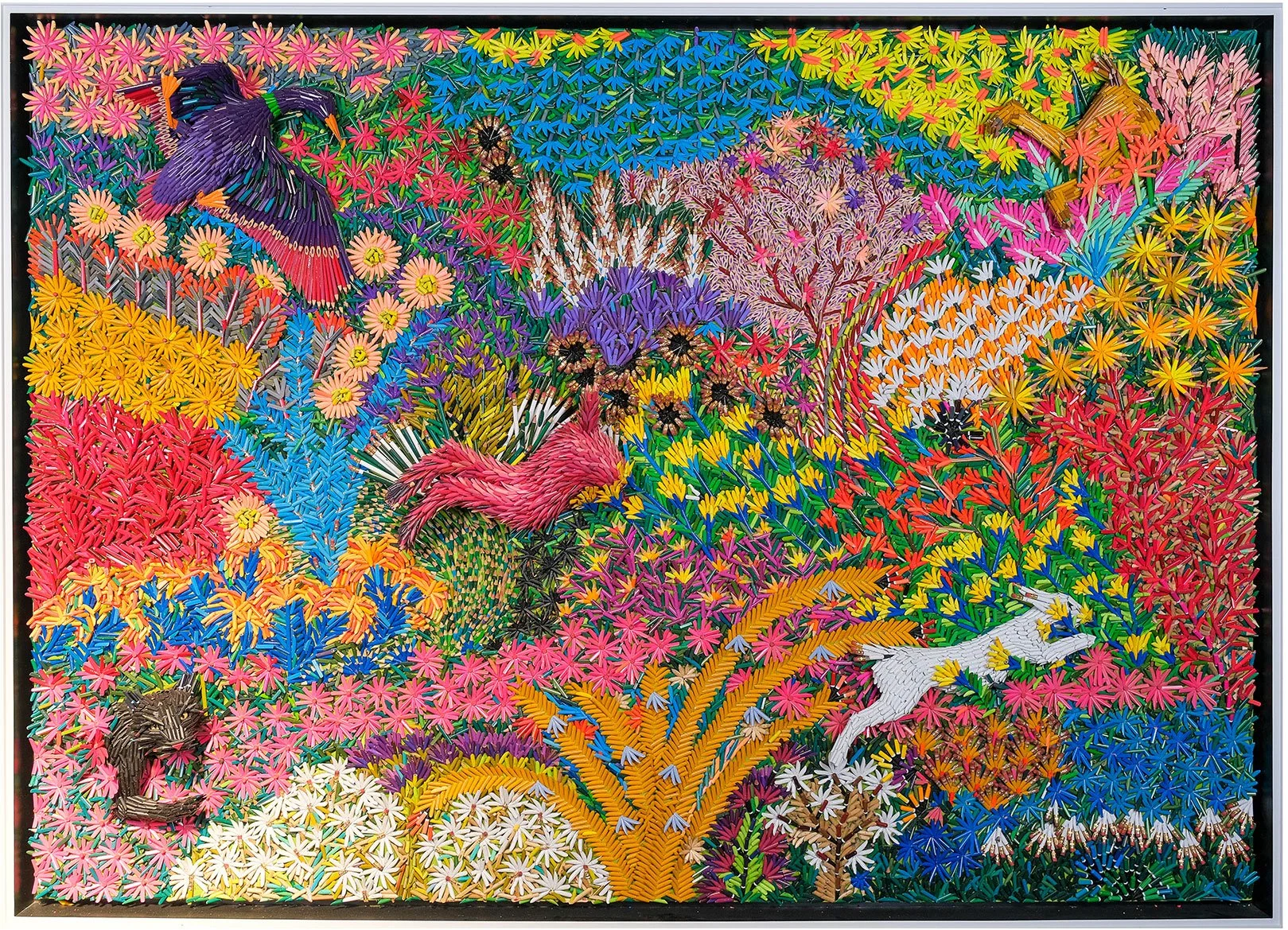

Born in Bogata, Colombia, Federico was living in Mexico as a painter when one day, he says, “I just couldn’t paint anymore. I couldn’t find images in my head.” After asking a housekeeper to teach him how to embroider, and visiting stores that sold not only needles and threads, but supplies for toy- and doll-making, he started sculpting with plastic utensils and baby bottle nipples recalled by the manufacturer. “And I understood that that was my real calling — this sort of painting with objects that are not necessarily meant to be for paintings.”

Uribe went on to blend shoelaces and neckties, coins and books, guitar strings and broken colored pencils, into his unique creations and, after moving to Miami, found a way to tell stories through an unlikely item. “I had access to bullet [shells], which I never had before. … Now I’m obsessed with the idea of connotations that we all have towards objects. Working with bullets or surgical instruments or

X-rays or Band-Aids that have this connotation of pain is a challenge for me to change the reading of these objects towards a more positive [one].”

Such items also allow Uribe to express his convictions. Right now, for instance, he is sculpting animals out of screws “because animals get screwed. … It was an intentional statement about hunting, so creating a beautiful animal out of bullets, the only thing that destroys it, was a good idea in my eyes. Now I’m [using screws to make animals] because climate change is destroying the forests with fires, and changing weather patterns are killing animals.”

For Uribe, it’s not about recycling. It’s about the message behind the art. “People kill trees to make books, so I disassemble books to make tree [sculptures]. I disassemble furniture and other objects made out of wood to make a forest, trying to return things to their own origin. And I’m building an installation of suitcases about immigrants that probably won’t be shown in this administration. But I’m making it anyway.”

Frederico Uribe - Flowerscape, 2022 – Colored pencil collage (photo courtesy of the artist)

Zwia Lipkin

A decade ago, after studying art and Chinese

history, then taking a break from both, Zwia Lipkin discovered FabMo, a nonprofit organization in the San Francisco Bay area that rescues designer fabrics from the landfill. It was there that she fell in love with thick, colorful upholstery that appealed to her tactile side — “It just clicked, right there. It was exactly what I loved about art,” she says — and began making decorative bags, pillows and other functional pieces before later deciding to work exclusively with repurposed fabrics.

The concept of reusing castaway items was nothing new for Lipkin. Her father, who was always fixing or building something in the family’s home in Israel, often collected screws and pieces of wood he spotted on the street to make something new. In high school art classes, Lipkin incorporated found objects into her pieces and even wrote her senior thesis on the use of trash in modern art. “I made things from old antennae that I found broken on the street and shoes that someone threw away,” she recalls.

In another nod to her dad, a marine biologist, she created “Blue Planet Blues” with empty single-use plastic bottles as a warning about their impact on the world’s seas. “After he passed away, I read all these articles about microplastics and big trash patches floating in the ocean,” she says. “And I realized he would’ve been devastated if he were alive.” The piece now hangs in a university in Ukiah, California.

In addition to conserving, recycling and composting in her daily life, Lipkin maintains a zero-waste studio. “The border between finding beauty in everything and becoming a hoarder is really thin,” she says with a laugh. “I keep every tiny bit of scrap that I have from my fabrics, and often I make other things with it later. Sometimes something waits in my studio for five, six years, and then I

can find the perfect use for it. And that’s a great feeling.”

Zwia Lipkin - Blue Planet Blues, 2021 (photo courtesy of the artist)

Materials:Home décor textiles, embroidery floss, ink, buttons, plastic bottles

Techniques:Stamped, raw-edge pieced, raw-edge appliquéd, machine stitched, hand embroidered

Lina Puerta

For the naturally curious Lina Puerta, experimenting with different materials, mediums and techniques is central to her art. “That sense of exploration has shaped my style more than anything else,” says the Colombian-American artist, who creates mixed-media sculptures, installations, collages, handmade-paper paintings and wall hangings with found, personal and recycled objects. “I often work in series, which allows me to go deep into an idea, and I think of my style as a kind of language — one that has grown, become richer and expanded over time.”

As a young teenager, Puerta loved making collages from wrapping papers with textures, colors or patterns that caught her eye. Early in her adult career, she focused on what she calls “anatomical and botanical hybrids,” with artificial plants providing a backdrop for scenes captured in suitcases and bell jars and punctuated by lace, sequined fabrics and jewelry. Today, the New York artist’s tapestries, pulp paintings and quilted hangings frequently illustrate themes of food justice, the environment and the hardships of farm workers.

Puerta acquires many of her “ingredients” from Materials for the Arts, a New York City agency that collects surplus supplies and makes them available to arts organizations. “I’ve found so many unexpected treasures there,” she says. “I also use found

objects I come across on the street, or my own personal items that hold sentimental value.”

Giving existing materials new life is important to Puerta “in a society of overproduction and hyper-consumption, which creates enormous amounts of waste and an imbalance that affects the entire planet. By reusing materials, I’m trying to resist that cycle. I also find that materials have their own energy which helps guide my creative process.”

Lina Puerta - Untitled (with Kuna Mola), 2018

concrete; repurposed wood, aluminum, acrylic sheeting, polyurethane, acrylic paint, paper pulp, leather scraps, lace, sequined fabrics, faux fur, Swarovski crystals and beads; chains from broken jewelry; and found indigenous Kuna Mola (Panama/Colombia).

Lydia Ricci

At a young age, Lydia Ricci learned from her parents the value of making something out of nothing. Her resourceful mom, an immigrant from Ukraine, was constantly tinkering around the house, and her dad, an Italian from South Philly, was “the guy who kept everything. There were always industrious things going on, maybe not with the right tools and maybe not in the most meticulous manner, and maybe the job didn’t always get finished, either. … I didn’t realize how inspirational all that would become.”

Moving to San Francisco at 21, she scoured thrift stores and raided other people’s trash for discarded trinkets to make her place feel homier. “If there was a lamp on the sidewalk, I grabbed it even if it was broken, just because it kind of looked pretty.”

Ricci was employed as a graphic designer when she made her first upcycled piece, a box-turned-car that resembled her family’s unpredictable green Dodge. More automobiles followed, along with different sculptures fashioned from old tax forms and address books, hair dryers and wires. In the beginning, most were miniatures, although that wasn’t intentional, she says.

“Once I made one thing, it was all I really wanted to do,” says Ricci, who lives in Pennsylvania. One of her favorites: a vintage cash register sparked by her childhood fascination with pushing buttons and her grandfather’s habit of squirreling away his scribbled expense lists. “I can’t always articulate why I love something, like an old toilet package that’s bright green and has a dent in it, but it’s more important than a fancy purse or

a piece of jewelry. I find my materials to

be jewels.”

“The Dodge,” Ricci’s first upcycled piece (photo courtesy of the artist)

Stephanie Lynn Daigle

Unhappy in her role as an artist for a grocery chain, Connecticut resident Stephanie Lynn Daigle abruptly quit her job in 2017 to freelance. But without a steady income, no money for supplies, and the influence of trash sculptors she’d been following on Instagram, she set out to craft her first upcycled piece: a blue stag she named Yondu. A wall-art deer, she thought, would probably sell because it “seemed like something that someone might want in their home. … And because it was already made of trash in a different, unorthodox way, let’s make it extra funky.”

After much trial and error, and the intuitive placement of scrap materials attached to wood with tape, screws and glue, Daigle says, “I got really, really excited. Art seemed so much more creative than it ever had to me. It always felt more like an assignment or a job prior to then. I was like, ‘I can’t believe that I took this long to find this.’”

Friends and family began saving their recyclables and interesting “junk,” and Daigle collected everything from Tupperware to purses she’d never gotten around to throwing away. Soon, there was no turning back. At first, she worked solely on commission so she could focus on making a living. She has since come full-circle, sculpting animals ranging from ostriches and giraffes to seahorses and her bestselling octopuses.

“Not only do I love animals and I just have a fondness for the natural world, if you make something like a car or a motorcycle out of junk plastic, it looks a lot more of the same of what it already looks like, because these are manmade things. But if you’re making an animal, these are organic shapes and they’re rounded. They have a completely different aesthetic because they take on a steampunk look.”

Stephanie Lynn Daigle - Prudence - Strawberry cow made from discarded plastic

Aurora Robson

Only about 5% of plastics are recycled in the U.S., according to environmental experts, with the rest finding their way into nature for centuries or into our bodies as microplastics. Aurora Robson uses art to bring attention to this issue, and last fall curated the exhibit “Plasticulture: The Rise of Sustainable Practices with Polymers” at the SVA Chelsea Gallery in New York.

“I love the idea of trying to bring people’s attention to work that’s kind of radical in this way that’s not pandering to the typical 1% of the human population who can afford to engage in art as a luxury item,” Robson says. “I want to use this mode of expression to raise awareness and inspire action around plastic pollution so that hopefully more creative stewardship initiatives will proliferate and potentially combat this problem.”

The “Plasticulture” exhibit featured

45 works by 15 artists from Project Vortex, an international collective of artists innovating with plastic debris. Robson founded the collective in 2009, a group that currently has more than 40 members across three continents who are all finding new ways to intercept and repurpose the plastic waste stream. Most were sculptures made of plastic debris, some suspended from the ceiling and

others spilling from the wall across the floor. The artists created animals, landscapes, clothing and more out of the would-be trash, resulting in colorful and impactful statements.

“The idea initially was just to sort of find a way to continue doing the work I was doing without feeling like I was working in a silo or completely by myself tackling this depressing problem,” Robson says. “I felt a deep need for more of a community with any other artists working with this material and how we could potentially support each other and amplify our voices. … Working this way can be so therapeutic for creatives. It helps you recognize and utilize your power and agency.” —Additional reporting by Sarah Prager

Various pieces featured in the “Plasticulture” exhibit by Project Vortex (photo courtesy of Aurora Robson)