A Dream Deferred, then Realized

Photo: BlueOrigin

Although Ed Dwight was chosen by President John F. Kennedy to become America’s first Black astronaut candidate in 1961, Dwight had to wait until 2024 to make his inaugural journey into space, ultimately earning the distinction of becoming the oldest person ever to participate in a space flight. While it wasn’t exactly the honor he had originally hoped to achieve, he was thrilled, nonetheless.

At age 90, Dwight was one of six participants aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket. “They treated me like a 90-year-old guy,” he says of the other crew members. “They made sure I was comfortable in my seat. That was kind of fun. The flight itself, parts of it surprised me. When the booster left, I just knew the thing exploded and we were all dead,” he adds, laughing.

In addition to being surprised about aspects of the flight itself, Dwight also found the views of Earth to be perhaps more spiritual than he had anticipated: “Seeing how beautiful, phenomenal — no dividing line between the states or countries — why can’t people get along with each other?!” he questioned. Crew members experienced a short period of weightlessness as the rocket reached more than 347,000 feet, and when Dwight returned to Earth, he triumphantly shook his fists in the air.

Although Dwight’s life would certainly have turned out very differently if he had made his inaugural space journey 50 years ago, leaving the space program allowed him to pursue other careers, including as a computer systems engineer at IBM, a real estate developer and restaurateur. But Dwight’s most important career alternative to astronaut is the one he is still engaged in today: as an artist. “I was born to make art,” he says. Since the age of 2, Dwight has always known that he was an artist at heart. “Here I was in preschool, and the other kids were drawing stick figures, and I was drawing real people,” he remembers.

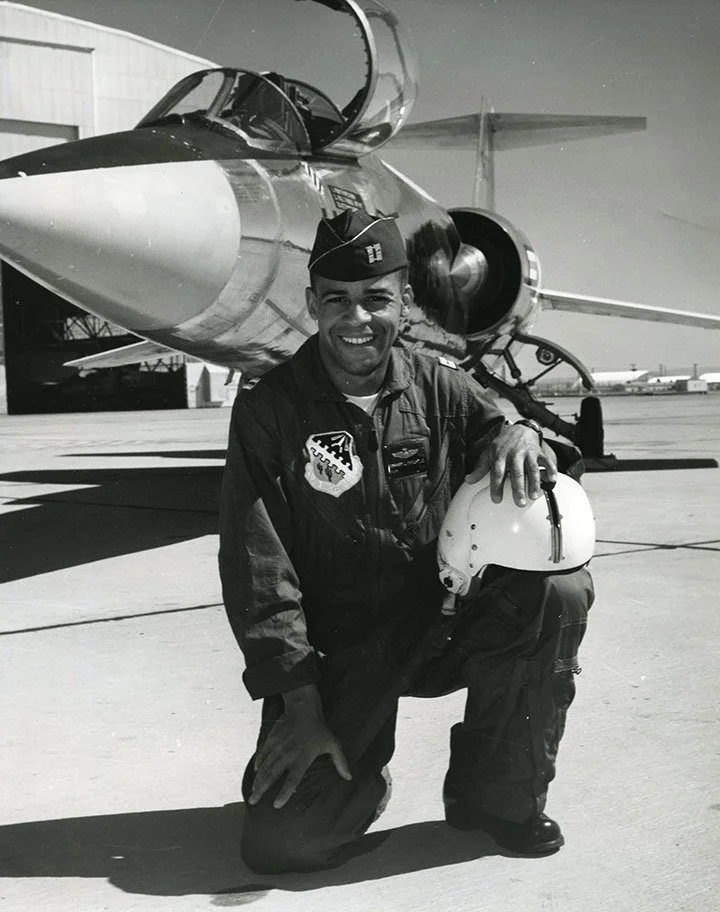

A younger Dwight poses with a jet during his time in the U.S. Air Force, on a different path than art school. (Courtesy of Christopher Dwight)

In addition to spending time drawing, Dwight was also learning about planes at an early age, working at an airport outside his hometown of Kansas City, Kansas. “They put me to work,” he says of the pilots there. “3, 4, 5 years old and I was working cleaning out airplanes.” The enterprising young Dwight also had a paper route once he was a bit older, and one day, he saw a Black American World War II pilot on the front page of a paper he was delivering.

“They’re letting us fly!” he remembers thinking, a life-changing realization. Seeing that photograph opened the world of flying in service to his country as a legitimate career possibility to Dwight. He enrolled in the U.S. Air Force instead of taking an art scholarship he was offered to the Kansas City Art Institute, easily passing the required tests. “The Air Force declared me a genius, but I’d just been studying,” he says modestly, referencing count-less hours he had spent in

the library reading Air Force training manuals.

As part of an initiative to increase the number of Black students pursuing science and math during the height of the civil rights movement, President Kennedy wanted a Black astronaut to serve as a role model to Black students, showing where STEM could take them, and he chose Dwight as the first Black astronaut candidate. Dwight was thrilled at the prospect, but explains, “I lost my sponsor when he was assassinated.” He soon found himself out of the astronaut training program, and out of the military as he says the rush to dramatically increase the number of Blacks in STEM died along with Kennedy.

Joining the private sector, Dwight worked at IBM as an engineer, then as a construction entrepreneur, and then started a restaurant chain because, as a Kansas City native living in Denver, he says that “there was no good BBQ in Denver.”

Honoring Black History

In retrospect, those careers helped Dwight mature, gain skills and network until the opportunity arose to pursue his lifelong dream of becoming a professional artist. That opportunity was named George Brown, the first Black lieutenant governor of Colorado. Brown had been to Dwight’s home and had seen Dwight’s paintings and his sculptures made from scrap metal from his construction business. Brown commissioned Dwight to create a public sculpture in Denver, and Dwight, ever modest, turned him down, saying, “I will make a fool out of both of us.” Brown persevered, imploring Dwight to teach himself how to sculpt figures.

Dwight realized he had never seen public art created by a Black artist or depicting Black people contributing to the formation of the United States. “I didn’t think Black people did anything,” he admits, adding, “I thought he was crazy. So I flew to Atlanta, Chicago, New York and I couldn’t find any Black public art.”

Dwight also researched Black history, learning about the contributions of Black people such as Harriet Tubman and George Washington Carver. “I hadn’t heard of any of them … But I looked at the need for public art and the recognition that Black people did contribute enormously to this country; I had a new ambition and inspiration,” he says.

Photo: Kansas Tourism

To date, Dwight has created more than 133 public art pieces that are on display in 38 states. The Texas African American History Memorial, an outdoor monument more than 50 feet long and installed on the Texas State Capitol Grounds in Austin in 2016, is one of his most notable works, depicting an array of people and events in Black American history from the 1500s to the present. Other large scale public works depict such critical movements and groups in Black history as the Underground Railroad, and various Black soldiers in World War II, including the Tuskegee Airmen. Dwight has also publicly memorialized dozens of Black individuals of historical importance including everyone from George Brown, Dr. Martin Luther King, George Washington Carver, Frederick Douglas and Alex Haley to B.B. King, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Hank Aaron.

In addition to the public, largely outdoor works erected on college campuses and in public spaces around the country, Dwight also has sculpted hundreds of smaller pieces that reside in galleries and private collections, some in the homes of the well-known politicians and entertainers Dwight counts as both friends and patrons.

“Nelson Mandela was one of my best friends,” he says. “He owns five of my pieces.” Dwight also has formed relationships with poet Maya Angelou, producer Quincy Jones, musician and bandleader Dizzy Gilespie and others, many of whom he counts as friends, collectors and subjects. Stories of his interactions with them drop easily: Sentences such as “Bobby Kennedy was in my living room three days before he died” and “Strom Thurmond hugged me and wished me well” pepper his conversations.

At age 91, Dwight has big plans. He is working on at least one more book (“Ed Dwight: Soaring on the Wings of a Dream” was published in 2009), hopes to open a museum, start a podcast, continue creating art and, notably, return to space.

“Of course, of course,” Dwight replies when asked if he’d like to go into space again. “I would like to go into orbit,” he explains. “You can see the Earth from a different perspective. When you go up and down, you only see half. That would be the reason I’d want to go — to see the whole Earth.” nA